Story beginnings are tough; even I can recognize that.

When I’m getting ready to start a new writing project, I spend a lot of time developing and getting to know the main character. One of the things I do is write a character monologue to help get a sense of his/her voice.

When I’m getting ready to start a new writing project, I spend a lot of time developing and getting to know the main character. One of the things I do is write a character monologue to help get a sense of his/her voice.

With my WIP, I had the brilliant idea to include this monologue as the novel’s opening – a decision for which members of my writing group rightly called me out when I read it to them. Comments included,

“Nothing happened.”

“I was bored.”

“There was no action; it was just a bunch of information that didn’t mean anything to me yet.”

“I found it rather poignant.”

(I think I fell in love a bit with the guy who said that last one. However he was already taken, plus he eventually quit writing and gave up the group, which suggests he didn’t really know enough about writing craft to give me proper advice.)

Since that incident, I’ve become hyper-aware of how books and shows begin in search of useful tips I can employ when it comes time to rewrite my own beginning.

Recently, I found myself examining the opening of TV’s Outlander while watching the pilot episode with a friend.

15 minutes of frustration

For those not familiar, Outlander (based on a highly successful historical fiction series by author Diana Gabaldon) is the story of Claire – a nurse during WWII (which has just ended) – who is transported back in time to 18th-century Scotland in the midst of civil war and into the clutches of a dashing Highland warrior.

That is an interesting premise, and should’ve made for interesting viewing, especially for a costume drama buff like me.

My friend and I didn’t make it past 15 minutes.

All through that time, I kept waiting for something to happen. Sure, a number of events took place, but it was all setup. None of it demonstrated any conflict.

And conflict is what drives a story – what makes it fun to read or watch.

For 15 minutes straight, I identified instance after instance of where I expected conflict to occur:

- Claire could’ve been shown to be an ineffective WWII nurse

- She could’ve been unhappy the war ended because she now had to return home to her husband, Frank

- She and Frank – who she’d not seen for five years during war – could’ve been awkward around each other

- Either Claire or Frank could’ve not wanted to go on the trip they took to Scotland to get reacquainted

- The matronly housekeeper at the house where they stayed could’ve disliked them, for whatever reason

- Frank could’ve been annoyed by Claire’s attempts to scandalize the housekeeper by jumping on the squeaky bed.

Just to name six. My actual list was much longer.

But none of these things happened. What did happen was that Claire and Frank (and also the housekeeper) got on hunky-dory.

Claire was charming and perfect (and to be honest, perfectly dull) in everything she did, nothing bad happened, and if I hadn’t roughly known what Outlander was about going in, I’d have had no idea what I was watching or what to expect.

Opening the mind what’s possible

A good opening needs to cue its audience – needs to pose questions in the reader or viewer’s mind (other than “What the hell am I reading/watching?”) about what’s going to happen and the type of problems the story is going to address, and why. Inherent to those questions is the promise that they will indeed be answered by the story’s end.

The conventional wisdom of writing states a story should begin in medias res. This literally means “in the middle of things”, or more generally, that a story should begin with action and conflict and a strong hook.

This doesn’t have to be a car chase or a murder – conflict can takes many shapes and sizes – but it should be something that gives a sense of things to come.

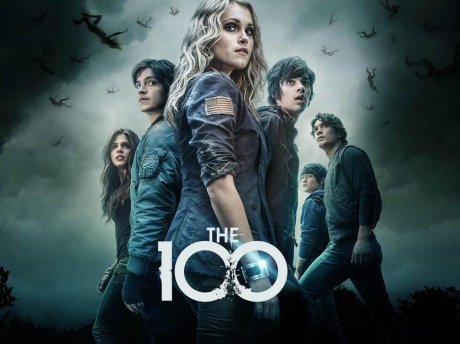

Compare Outlander’s opening with that of another show I recently watched, The 100, which is on Netflix.

Compare Outlander’s opening with that of another show I recently watched, The 100, which is on Netflix.

This show takes place in the future on a space station orbiting an Earth that was poisoned by nuclear war some 70 years ago. The station’s inhabitants have been waiting generations to return to Earth, but don’t know if it’s yet recovered enough to support human life.

The 100 opens with 100 of the station’s previously incarcerated juvenile delinquents being sent down to Earth (with very few provisions) to earn exoneration for their crimes by determining if the planet is survivable.

It’s an utterly preposterous premise. But, it made me ask (admittedly incredulous) questions about what was going to happen, not the least of which was, “How does anyone think this is even remotely a good idea?”

And why does everyone’s hair look so good after a week in the wilderness with no shampoo or plumbing or mirrors?

Which is still a better questions than, “What’s this thing even about?”

What are your thoughts on story openings? What are some good examples you’ve come across? Do you struggle with your own openings? Let me know in the comments.

(A/N: FYI, I do plan to go back and continue watching, for the show is getting great reviews and I am, unabashedly, a costume drama buff.)

(Image source #1 and #2)

I find it interesting that we (writers) are regularly advised to begin with action/excitement when so few books and shows actually do that. I’m reading a Rhys Bowen novel in which almost nothing happens until page 118 (I was carefully monitoring the story, as I am anuable to simple enjoy something. I must analyze)… save for the heroine being broke and vaguely concerned that she would be placed into an arranged marriage at an undetermined moment in the future. I actually like the book and don’t mind that it tok so long for the plot to kick in, but I wonder what would happen if I submitted such a thing to an agent.

I’ve tried all different kinds of openings. Intrigue; an artful contruction; ironcally banal; an unexpected moment/location. I’m not sure if any of it works. I’m going for intrigue in the open of my WiP, though people will already know the premise. It is was it is. I like my first chapter.

LikeLike

When I say “action” (and I purposely only used it once in this post, and purposely not in the title), I don’t mean of the sort found in action movies, which are often over the top. Rather, I mean it in its most general form: something active taking place rather than something passive. I think of some of those British dramas where characters give each other withering looks from across a room. That is action – it’s a source of conflict, and raises questions and speculation and excitement.

My WIP (when I actually get around to rewriting the opening) will an important character being long overdue in returning home and negative consequences that result from his absence. As a reader, my tolerance fluctuates for books that start slowly; whether I’ll continue reading depends on so many other factors: whether I’ve read the author before; whether review indicate the book picks up; the writing quality; how interesting in general the subject matter is to me.

That said, when it comes to us as writers – particularly debut authors – I doubt many of us will have the luxury of 100 pages to get things cooking.

LikeLike

As future debut authors, we have to just write the best thing we can write and hope it clicks with someone.

LikeLike

Amen, brother!

LikeLike

Oh yes. Conflict and questions right away. In the title, the prologue (145 words of WTH? RELATED to the book), in the beginning not just of every chapter, but every scene.

Donald Maass wrote a book I use daily (though maybe not as he would use it) called The Fire in Fiction. I find two chapters especially helpful: 3. Scenes that can’t be cut, and 8. Tension all the time. If the first and last lines of a scene aren’t a hook for the scene, and the next one by asking questions in the reader, answering some, and then leaving more, I haven’t done my job.

Sol Stein talks about chapter which are crucibles: all the character you want are together, stuck, where they can’t get away from each other. I make sure every chance I have that crucibles appear and are used. For example, say you have a scene where the hero goes to talk to his son’s teacher – don’t just have a scene that shows he loves the kid, bring in a connection he used to have to the teacher (now married and with a different name) that he doesn’t want anyone to know about – and you have created a crucible. I start the WIP with a pseudo-crucible (one person is on the other side of the country – but she watches the events on TV in real time).

Otherwise, why would you keep reading? Boring!

LikeLike

Ah – the prologue! I’m not 100% anti-prologue, but I do view every one I come across with a jaundiced eye. My very first novel (which I shelved) had one which I can now fully admit was info-dumping at its best (make that, worst). In my plans to rewrite that novel, I’m debating writing a new prologue, although I’m not married to the idea. I may just be wanting to do it to prove to myself that I can!

I agree with you (and Donald Maass) about the importance of scene-level conflict. Those hooks at the beginning and end are what hold the entire crazy quilt of a story together.

LikeLike

I don’t think a story really needs to start with ‘action’ but a ‘question’ or ‘conflict’ seems to be a good way to start. I usually try to put my characters in a situation they need to either resolve or escape from at the beginning of a story. I’m actually a very lazy reader and will give up unless i care about what happens to the characters. The start of a story is the hardest because you have to get it right and grab the readers attention from the get go. When I read The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo I thought it was incredibly boring for the first half, but I only kept going because I’d heard it was so good. Had I not been told how good it was I would have dropped it after half an hour.

LikeLike

Not action like an action movie; rather something active as opposed to something passive. As I was saying to Eric below, a withering look from across the room can be action.

I like your method of giving your characters a situation to resolve or escape at the beginning, because this seems like it would give you a chance to show what the main character is like in his/her normal life – s/he usually responds to problems – as a good point of reference for when s/he eventually changes and grows over the course of the plot.

LikeLike

Janna I’m surprised you remember the beginning of your WIP at this stage 🙂 I must admit it’s only now, at novel #4, it’s dawned on me that I need to get right into it or else I’ll lose the reader.

LikeLike

Roy, I remember everything; just ask a certain former co-worker of mine. When she got engaged and we held a little party for her at the office, I put together a “How well do you know Sarah?” quiz for us to play that contained trivia questions from all the personal stories she’d (over)shared over the years. I think she thought I hadn’t been listening because, as an introvert, my natural mode is to be quiet and process internally. I combined my two unlikely superpowers for just shy of evil that day. 😈

P.S. It was all in good fun; she and I are still friends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great insights. I mostly watch YouTube…but occasionally I watch Merlin or some home improvement or traveling show. 😀

LikeLike

Thanks. I don’t watch that much TV either. I don’t even own an actual TV set. I most just watch Netflix (only on the weekends), although I’ll occasionally watch a cable show at a friend’s house.

LikeLike