Life in the medieval times was the ultimate pyramid scheme. It was also a perilous numbers game in which, perhaps unsurprisingly, the number that trumped everything (except when it didn’t) was one.

In the history books, all of this is more commonly referred to as the feudal system, which was the dominant structure of society in England for some four hundred years, and in continental Europe, even longer.

In this first of three post on this subject, I’ll provide a general overview of what the feudal system was.

The term “feudal” is not one from the era in which the system actually existed.

Rather, it was coined during the 17th century, coming from the Latin word feudum, which has a Germanic origin in the word feoh, meaning cattle or property. “Feoh” is also related to the modern word “fee”, which was a word used historically in this system.

According to Joseph and Frances Gies, authors of Life in a Medieval Castle, the feudal system comprised of,

[T]he sworn reciprocal obligations of two men, a lord and a vassal, backed economically by their control of the principal form of wealth: land. (p.32)

They go on to explain that,

[T]he land [was] granted by the lord in return for the vassal’s service, or more technically, a complex of rights over the land, which theoretically remained in the legal possession of the lord. (p.45)

Another way to think of a vassal is thus as a tenant living in a lord’s rental property, albeit a property with rents that are substantially different from those collected by modern landlords.

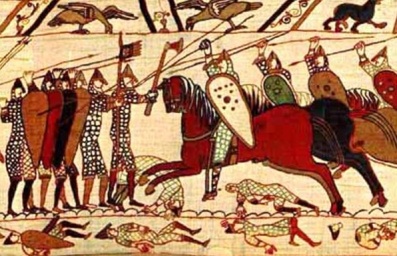

Imported by force

Feudalism was imported to England by William the Conqueror following the Norman invasion of 1066, not only because it was the system he – as well as much of Western Europe – was used to, but also because feudalism lent itself well to the further suppression of the native English (Saxon) people.

Upon assuming kingship of England, William immediately laid claim to all the secular land (and its inhabitants) of the kingdom, including that previously belonging to Saxon lords.

Retaining approximately one-fifth of England as part of the royal demense (i.e. domain), William then distributed what remained to be held (but not owned) by his key barons and noble supporters to manage, maintain, and, ultimately, subdue, the imposition of the feudal system in England coinciding with the construction of numerous new castles where, pre-Conquest, there’d been only six.

However, these land grants given out by King William to his Norman favourites would have been vast (the Gieses estimate that William’s eleven chief barons together held nearly one-quarter of all England, each, with grants running to hundreds of square miles).

While surely an honour to hold so much land of the king, practically, such a grant would have proven far too difficult for a single lord to administer on his own.

The solution to this (which from the year 1100 onwards became very well-established and advanced) was subinfeudation. Also not a medieval term, subinfeudation describes the process by which an earl or baron who was a vassal of the king re-parcelled some of that land to lesser nobleman, to whom he in turn became lord and they his vassals.

Sometimes, this subinfeudation occurred several levels down, thereby further extending the hierarchical pyramid in which the king was at the very top and lowborn peasants (“villeins” in England; “serfs” on the Continent) made up the very bottom.

A fee of service

The land granted by a lord to a vassal under the feudal system was called a fief, which related to a fee of service from a given number of knights (“knight’s fees”) owed to the lord each year as payment for the land.

The size of each fee was proportional to the extent of the land: a great baron might owe a fee of hundreds of knights whereas a much lower-ranked nobleman might owe only the service of himself, the cost of furnishing himself with a warhorse, armour, and all a knight’s necessary equipment, weapons, and attendants representing a significant ongoing expense.

A vassal’s investiture to his fief occurred by way of a commendation ceremony and a formal oath of loyalty and service (fealty) sworn by a vassal to his lord. An example oath, quoted in Life in a Medieval Castle, is as follows:

“I promise by my faith that from this time forward I will be faithful to Count William and will maintain toward him my homage entirely against every man, in good faith and without any deception.” (p. 46)

The oath would be sworn upon a religious relic of some sort (e.g. a bone or scrap of clothing from a saint) and performed immediate after the commendation ritual, which involved the vassal placing his two hands between the hands of his lord to represent their alliance, and was then often also sealed with a ceremonial kiss.

Ostensibly, the feudal contract, once entered, was not lightly broken, but in reality, this didn’t always prove the case. As well, the investiture was meant to be hereditary, but there were certain considerations associated with that as well. Both of these points will be discussed in my future posts on the feudal system.

Let’s not fight

A “knight’s fee” as a form of payment has an undeniable military connotation.

Indeed, the Gieses state that the feudal system “…originated as a simple economic arrangement designed to meet a military problem in an age when money was scarce” (p. 45), and that it existed in one form or another as early as the late Roman times.

However military service didn’t always mean fighting wars. In fact, many barons and knights spent a significant amount of time trying to avoid going to war, more than once even rebelling against the king and his insistence that they participate in foreign wars that they perceived as beyond the scope of their feudal obligations.

According to the Gieses,

[M]ore than their much advertised love of fighting, [barons’] dedication to getting, keeping, and enlarging their estates dominated their lives. Estate management itself … was extremely demanding. No lord, however fond of fighting, could afford to neglect his estates. (p.39)

In my remaining two posts on the feudal system, I’ll explain the full range of services a vassal was obliged to provide to his lord, as well as what the lord owed his vassals in exchange.

I’ll also discuss how various types of medieval people fared differently under the feudal system.

Read all Medieval Mondays posts

(Image source #1, #2, and #3)

Was the kiss not a romantic gesture during this time period?

LikeLike

Kissing was romantic, however in this instance, it was ceremonial. It doesn’t indicate the precise nature of the kiss in any of my reference books, but I’ve envisioned it as a kiss on the cheek near the mouth the way French people greet each other. Since the English nobility was actually of French (Norman) descent, this makes sense to me.

LikeLike

Thanks for this enlightening piece Janna. Here in Jersey we retain our Fiefs and Seigneurs though they are of course mainly ceremonial these days. However we had a fascinating legal case not so long ago where the ancient rights of a Seigneur were defended and the out-of-court settlement in his favour was substantial.

LikeLike

I would have been following that case closely were I there. I always find it interesting when ancient/historical rights and concepts are asserted in the present day, for the outcome, at times, is unbelievable.

LikeLike

Certainly in this case the ancient customary law would almost certainly have won out in Court had it gone the distance. It concerned ownership of the foreshore adjacent to the fief.

LikeLike