This post is more accurately titled “Should Female Writers Abbreviate Their Names?”, since they are, it seems, the writers who most commonly do so.

The short and simply answer to the question is, of course, “They should do whatever they want.” For I’m not here to dictate otherwise, especially given the numerous different reasons a female writer would choose to use her initials instead of her full name:

- She had a given name that’s difficult to pronounce or spell

- To create a new identify for writing in a different genre

- To maintain a measure of distance from her non-writing life

- Because another author has her exact same name

- Because she dislikes for her given name

- To emulate classical male writers who used abbreviations, such as C.S. Forrester, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and J.D. Salinger

Just to name a few.

There is, however, another reason some female authors might abbreviate their names – a reason that, I’m not gonna lie, irritates me every time I hear about it.

That being, as a means of disguising their sex. Because they feel they have to to achieve both success and respect within their genres.

What’s in a name?

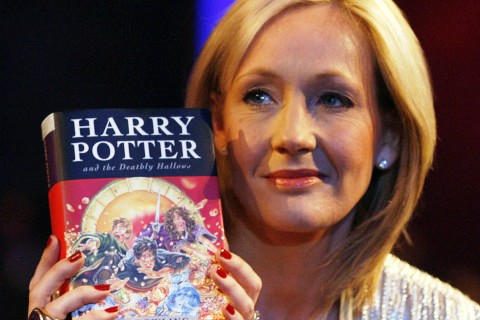

From the Bronte sisters – Ellis (Emily), Acton (Anne), and Currer (Charlotte) Bell – to Andre (Alice Mary) Norton, from A.M. Barnard (Louisa May Alcott) to V.C. (Cleo Virginia) Andrews, from C.J. (Carolyn Janice) Cherryh to Harry Potter author, J.K. (Joanne) Rowling (who also writes mysteries under the name Robert Galbraith), there’s a grand tradition in writing of female authors using male pseudonyms and initials to conceal their sex.

It’s a trend that continues to this day, particularly among certain segments of up-and-coming female writers, both traditionally and self-published.

It’s a trend that continues to this day, particularly among certain segments of up-and-coming female writers, both traditionally and self-published.

The reasoning for Rowling’s abbreviated name is as well-known as it is unapologetic. Simply put, it was done for fear that boys wouldn’t read a book written by a female author. This in spite of the fact that Harry Potter’s eponymous main character is male.

(Sci-fi great C.J. Cherryh’s name was abbreviated for the exact same reason back in the 1970s, incidentally.)

Whenever I hear the story about Rowling, I get a little more annoyed each time. And the same question keeps popping into my head:

Why are female writers and their publishers so eager to accommodate male readers?

Once my irritation subsides a bit, the question becomes more of an academic one, with full respect for all the men who are worthy of being respected.

It’s long been demonstrated by what may well be the most successful genres of all time – i.e. romance – that writing for female readers can be profitable.

Admittedly, not all writers enjoy such overtly female-centric, formula-heavy storytelling conventions. There are many female writers who instead prefer genres more traditionally read (and written) by men, e.g. mystery, thriller, and sci-fi, to name a but few in which I notice the greatest proportion of abbreviated female names.

Yet even for female writers of these more male-centric genres, the reading audience may well still be female, for studies apparently claim that women comprise 80% of fiction readers in North America and Britain.

So why is it so important for female writing to impress the few and the proud male readers? Why are female writers willing to diminish their very names – to delete any trace of their femaleness from their book covers – for the benefit of those male readers who would never knowingly read a book written by a woman?

Second-class writers

Of course, I already know the answer to these questions.

There are countless historic and societal factors at play. Historically, literature was the exclusive purview of men, both writing and reading it. Given that even women just reading often resulted in scandal among family members and the wider community, any woman wanting to write had no choice but to pretend to be a man.

There are countless historic and societal factors at play. Historically, literature was the exclusive purview of men, both writing and reading it. Given that even women just reading often resulted in scandal among family members and the wider community, any woman wanting to write had no choice but to pretend to be a man.

Societally, books by male writers tend to win more awards, from such genre- and geographically-specific prizes as the Edgar Allen Poe Award for Best Mystery Novel to the international Nobel Prize in Literature. The Nobel winner for 2013 – Canadian author Alice Munro – is only the 13th woman to win in the award’s 114-year history.

Male-centric genres and writing are also taken more seriously. The mystery and thriller genres are seen as timeless whereas romance – which has been around just as long, if not longer – is considered frivolous except when a male writer like Nicholas Sparks (or in the case of YA, John Green) arrives to “save” the genre from itself.

Women are perceived to write about relationships and feelings and all the other female eccentricities that men dislike and don’t understand, to the equal disdain of those troglodytic knuckle-draggers who believe a woman’s proper role is to make him a sandwich right on up to University of Toronto English professor, David “I’m not interested in teaching books by women. What I teach is guys. Serious heterosexual guys” Gilmour.

It’s a sad attitude for both men and society to take regarding women’s writing, for exposing oneself to new ideas and experiences – particularly the ideas and experiences of 50% of the world’s population – and empathizing with ways of life that are different from one’s own can literally make the world a better place.

Say my name

I don’t ever want abbreviate my name in my writing as a means of concealing my sex.

Because as much as I want all readers to someday pick up my book, I want them to do so willingly, and with full knowledge of the fact that I’m female. I’m not interested in trying to trick anyone into reading my book. If a male reader wouldn’t have otherwise even considered reading me, well then I don’t care. He’s not the reader I’m writing for.

It’s his loss.

I do, however, want to see my work published and read as much as the next writer. I recognize that I make the above statement from the relative safety of a genre (historical fiction) already abounding with successful female authors, and that the path forward has been paved for me already.

But is the solution for women writing the male-dominated genres to carry on with the masquerade in hopes that men will read and realize that books by women are enjoyable too?

But is the solution for women writing the male-dominated genres to carry on with the masquerade in hopes that men will read and realize that books by women are enjoyable too?

Is it for women to embrace the freedom of self-publishing and build a critical mass of successful fiction with female names on the cover beyond the confines of traditional publishing?

Is it for female writers to badger traditional publishing nonstop with their excellent writing submissions until the powers-that-be finally stand behind the entire author instead of just the first letter of her first and middle name?

Every female writer must examine both her publishing goals and personal values and choose for herself.

My goal with this post has been to help make that choice a fully informed one.

(Image source #1, #2, #3, and #4)

Yet another pet peeve you and I share. My thinking is this: if female writers who decide to use their initials instead of their oh-so-scandalous feminine first names would just stop doing that, maybe the publishing world would get over the whole idea of OMG WOMEN WRITING SUCCESSFUL BOOKS a whole lot quicker. And sexist males whose reading choices just shrunk before their eyes with all these female names littering the shelves (do these males even exist?), well, tell me why I should care?

LikeLike

What you describe is the ideal long-term outcome. But in the short-term, I really do get how difficult it can be for female authors of male-centric genres like mystery, thriller, and hard sf to get their work published and/or read. I have heard stories about magazines that willfully won’t accept stories by women, and the case of that University of Toronto professor was just mind-blowing. This is supposed to be an advocate of high learning and expansive thought.

I think it will take a unified campaign of the sort like #WeNeedDiverseBooks to really make it possible for female authors to go abbreviation-free. Unfortunately, as long as even one author feels her opportunities are being stifled through the use of her real name, all of our opportunities are being stifled.

LikeLike

Your name also has a nice rhythm, so why obscure that? It’s all part of the marketing.

As reader, I find that authors who go by initials tend to blur in my mind after a while. i want to remember the names of the writers i enjoy.

LikeLike

Having a good name is indeed good marketing. In my case, writing within a genre that’s full of successful female names doesn’t hurt either.

But I get what you say about initials getting blurry, especially if the author’s last name doesn’t really stand out. The only ones I really recall are the uber-famous ones, like E.L. James, or my favourite classic authors, like V.C. Andrews and C.S. Forester (author of the Horatio Hornblower series).

LikeLike

In Tanya Huff’s “Blood Ties” series, one of the main male characters is a romance writer that uses a female pseudonym. I barely look at romance novels, so I’m not an authority on the genre, but I don’t recall ever seeing an obviously male author’s name on a romance novel. I wonder how many men use female pen names to get their work published in stereotypically female genres?

I understand why the Brontes and others before the 1920s used male names – their works would never have been published if they hadn’t. Did their publishers even know who the real authors were? I can even understand why women sci-fi writers used male pseudonyms before the 1970s (because despite the big 1960s women’s lib movement, most men didn’t take women seriously then, and almost all the people in science careers at the time were male). But now? I doubt any boys would have even noticed (or cared) that Harry Potter was written by a girl. They also have a very different perspective on names. A few years ago, my nephew (now 15) thought “Sam” was a girl’s name!

I think women using pseudonyms just to hide their gender is worse than unnecessay. It perpetuates the notion than female authors (or works written by women) are inferior. But I’d love to know how many male authors are using female pen names to make money in genres that have predominantly female audiences.

LikeLike

Rhonda, there are definitely men who write romance. Nicholas Sparks for one (author of The Notebook), who is very successful. But in terms of category romances like Harlequin, which I think you’re actually referring to, men write those too. I read an article about it one time. The author featured was doing well but expressed concern that female readers mightn’t accept his books if they knew he was male. Personally, my take was that he was more concerned about what revealing his true identity would do for his own self-image (“a man who writes romance?), as I don’t recall him using his real male name in the article.

I actually think women would get a kick out our an openly male Harlequin author, especially if the books were well-written. He could become a media sensation, and he too would probably be credited with “saving” the genre.

Unfortunately, the perspective is still alive and well that women’s writing is inferior, especially within genres like hard sf and sff, which I know that you like. Female authors are accused of injecting too much character development and interpersonal relationship consideration. While I get that this might go against the historic conventions of the genre, genres are growing, blending, and changing all the time. The pushback from the speculative genres, though, can be mighty forceful indeed, to the point that a female author writing the greatest, hardest, most non-character driven sf book the world has ever known could be dismissed out of hand on account of her feminine name.

LikeLike

There are a few other considerations – depending on what your name actually is.

And something like J. K. Rowling has an additional bit: mystique. Joanne K. Rowling doesn’t have mystique. Joanne Rowling doesn’t have mystique, nor does J. Rowling.

Another consideration is how long your name is, and what happens when you abbreviate or suppress parts of it. Mine is Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt. But Butcher is my father’s name, and Ehrhardt is my husband’s – and neither is really mine. Ergo, I refuse to be A. B. Ehrhardt or A. Butcher Ehrhardt – not me.

I took the name legally when I married – because I was getting my PhD and didn’t wish to deal with Dr. Butcher for the rest of my life. I didn’t just take Ehrhardt, because I didn’t want to be Alicia Ehrhardt (try it out loud; please skip the joke) for the rest of my life – it’s bad enough as it is.

IOW, I have problems.

I would dearly love to publish under the single name ‘Liebja’ (which I invented as my writing name back when I was 14 a few centuries ago) but it looks a bit weird, and no one pronounces it right (lee-ebb-jah), where right is determined by me – since I invented it.

And it is coming to a decision point soon. I’ll probably just keep with the too long whole thing – and the world can suffer. At least I can already spell ‘Ehrhardt.’

Answers are not always obvious. I seriously considered joining the Stone gang (The Moon is Harsh Mistress), but I think Alicia Stone is taken.

I’m willing to listen to alternatives – but don’t have the energy to keep up a pseudonym (though it would be cool if I ever got to travel that way).

I have to remember to keep my TITLE short – for balance on book covers.

Good topic.

I’m noting with envy that you have all kinds of options, just like Rowling.

LikeLike

I feel like using initials once had mystique, but now it’s done so much – whatever the reason – that they all sort of blur together. To me, initials are not a name save for people who actually go by their initials day-to-day, like DJ or AJ or JF, and a name is the first step to a person becoming a friend.

But you’re right – married women often have the additional challenge of deciding what to call themselves. I’m not married, but my sister is, and she uses her maiden name professionally and both names the way you do for everything else.

That’s cool that you have a name that you gave yourself (although I’m glad you included the pronunciation guide, for I was hearing LEEB-jah). You need a diacritical mark in there somewhere. I actually think Alicia Butcher Ehrhardt has a very nice ring to it, and the somewhat complicated spelling of “Ehrhardt” (the extra “h”) balances nicely with the commonness of “Butcher” to give the whole thing a rather striking look.

LikeLike

Names are interesting – Martin Smith stuck his mother’s maiden name into his ordinary one, and got Martin Cruz Smith – which is way cooler.

I think I’m just going to go by the whole thing – me, dad, and husband – I think it will be easier in the long run.

Though I’ve thought of writing the mysteries as A. G. Butcher (Guadalupe being my middle name).

LikeLike

This is a great post, and it’s given me a lot to think about for my upcoming self-publishing endeavor. Thank you !!!!

LikeLike

I’m glad you liked it. It’s an important decision that every female writer needs to work out for herself.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Here’s Why JK Rowling Should Finally Drop the JK from Her Name and Go by Joanne